Background

The focus of my research is the origin and maintenance of marine biodiversity, particularly in coral reef fishes. My Ph.D. dissertation work was on the population genetics, systematics, and rates of molecular evolution of a group of small Neotropical reef fishes, the tube blenny genus Acanthemblemaria. My postdoctoral work focused on resolving and measuring the Acanthomorph Tree of Life.

While I am interested in all facets of marine biodiversity, at this point my lab's primary focus is on the group of fishes called blennies. Why blennies? My own work during and since my dissertation has found that these fishes are a fantastic model system to address a host of different evolutionary and ecological questions. Since I began my work, in a fortuitous turn of events, Near et al. (2013) found that blennies are one of the most exceptionally diverse groups of fishes living on reefs. My lab aims to understand this diversity at multiple levels of biological organization, ranging from molecular evolution at the level of the genome, population genetics at regional spatial scales, cryptic speciation and local endemism, to higher level molecular phylogenetics and systematics. We have a holistic approach to our research, combining genomic, computational, and classical genetic methods, with a healthy dose of field work.

We are part of the larger DEEPEND consortium, where my lab studies the taxonomic diversity and comparative historical demography of deep-sea fishes in the Gulf of Mexico. While I have focused on the biodiversity of reef fishes, we know next to nothing about the genetic diversity or cryptic species diversity in deep-sea fishes. This unexplored terrain is ideal for new discoveries and the formulation and testing of new hypotheses.

We have also begun an eDNA initiative in my lab. We are interested in the evolution of biodiversity in the ocean over geological time scales and eDNA provides a unique tool to accomplish this. We primarily work in the Gulf of Mexico, Belize, and Panama for these projects.

While I am interested in all facets of marine biodiversity, at this point my lab's primary focus is on the group of fishes called blennies. Why blennies? My own work during and since my dissertation has found that these fishes are a fantastic model system to address a host of different evolutionary and ecological questions. Since I began my work, in a fortuitous turn of events, Near et al. (2013) found that blennies are one of the most exceptionally diverse groups of fishes living on reefs. My lab aims to understand this diversity at multiple levels of biological organization, ranging from molecular evolution at the level of the genome, population genetics at regional spatial scales, cryptic speciation and local endemism, to higher level molecular phylogenetics and systematics. We have a holistic approach to our research, combining genomic, computational, and classical genetic methods, with a healthy dose of field work.

We are part of the larger DEEPEND consortium, where my lab studies the taxonomic diversity and comparative historical demography of deep-sea fishes in the Gulf of Mexico. While I have focused on the biodiversity of reef fishes, we know next to nothing about the genetic diversity or cryptic species diversity in deep-sea fishes. This unexplored terrain is ideal for new discoveries and the formulation and testing of new hypotheses.

We have also begun an eDNA initiative in my lab. We are interested in the evolution of biodiversity in the ocean over geological time scales and eDNA provides a unique tool to accomplish this. We primarily work in the Gulf of Mexico, Belize, and Panama for these projects.

Comparative Population Genomics

The primary focus of my population genetics research has been the tube blenny genus Acanthemblemaria, a clade of Neotropical coral reef fishes. In a comparative study of the two most widely distributed Caribbean species, I found that despite near identical life histories and distributions, one of the species, A. spinosa, a habitat specialist, has been able to persist through glacial cycles, while the other, A. aspera, a habitat generalist, has not. Signals of population expansions in these two species were obscured by the rapid rate of mitochondrial evolution in these fishes. However, by using both mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data, I was able to recover temporally separated population expansions.

Acanthemblemaria, as well as other blenny species, exhibit metapopulation dynamics, with populations "winking on" and "winking off" at different times and at different geographic scales. This provides us an opportunity to better understand the genetics of metapopulations in coral reef fishes and marine systems in general, but also allows us greater insight into how to conserve the cryptic marine biodiversity found on coral reefs.

We are now expanding our population genetics research beyond coral reef fishes, as part of our participation in the DEEPEND research consortium. Along with Mahmood Shivji, Professor at Nova Southeastern University, we will be studying the comparative population genetics of hundreds of deep-sea fish species. We will be doing this using both Sanger and RAD sequencing.

The primary focus of my population genetics research has been the tube blenny genus Acanthemblemaria, a clade of Neotropical coral reef fishes. In a comparative study of the two most widely distributed Caribbean species, I found that despite near identical life histories and distributions, one of the species, A. spinosa, a habitat specialist, has been able to persist through glacial cycles, while the other, A. aspera, a habitat generalist, has not. Signals of population expansions in these two species were obscured by the rapid rate of mitochondrial evolution in these fishes. However, by using both mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data, I was able to recover temporally separated population expansions.

Acanthemblemaria, as well as other blenny species, exhibit metapopulation dynamics, with populations "winking on" and "winking off" at different times and at different geographic scales. This provides us an opportunity to better understand the genetics of metapopulations in coral reef fishes and marine systems in general, but also allows us greater insight into how to conserve the cryptic marine biodiversity found on coral reefs.

We are now expanding our population genetics research beyond coral reef fishes, as part of our participation in the DEEPEND research consortium. Along with Mahmood Shivji, Professor at Nova Southeastern University, we will be studying the comparative population genetics of hundreds of deep-sea fish species. We will be doing this using both Sanger and RAD sequencing.

Cryptic Speciation

While we already know that blennies are one of the exceptionally species-rich groups of reef fishes, it has become clear that this diversity is most likely vastly underestimated. Recent work on blennies has shown that nominal species are in fact members of larger species complexes, often with limited distributions. My own work with Acanthemblemaria has found there to be very fine-scale endemism in the Caribbean, with some lineages restricted to localities <150 km apart from one another. We are following up this work with additional collections of specimens and genetic data, using RAD-Seq, as well as sequence capture, to discover species boundaries. We are actively working on species descriptions of these cryptic lineages, where character differences are subtle and easily missed. However, we are not only interested in finding these cryptic lineages, but are also interested in inferring their mode and mechanism of speciation. A central goal of my lab is to expand this work throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

We are now extending this work beyond blennies and other shallow-water fishes. Our new research program on deep-sea fishes has already begun to turn up cryptic taxa. This is not necessarily unexpected, given that there has been such a paucity of the genetic data useful for delimiting species. These discoveries are being followed up by species descriptions and taxonomic revisions of major deep-sea fish groups.

While we already know that blennies are one of the exceptionally species-rich groups of reef fishes, it has become clear that this diversity is most likely vastly underestimated. Recent work on blennies has shown that nominal species are in fact members of larger species complexes, often with limited distributions. My own work with Acanthemblemaria has found there to be very fine-scale endemism in the Caribbean, with some lineages restricted to localities <150 km apart from one another. We are following up this work with additional collections of specimens and genetic data, using RAD-Seq, as well as sequence capture, to discover species boundaries. We are actively working on species descriptions of these cryptic lineages, where character differences are subtle and easily missed. However, we are not only interested in finding these cryptic lineages, but are also interested in inferring their mode and mechanism of speciation. A central goal of my lab is to expand this work throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

We are now extending this work beyond blennies and other shallow-water fishes. Our new research program on deep-sea fishes has already begun to turn up cryptic taxa. This is not necessarily unexpected, given that there has been such a paucity of the genetic data useful for delimiting species. These discoveries are being followed up by species descriptions and taxonomic revisions of major deep-sea fish groups.

Phylogenomics

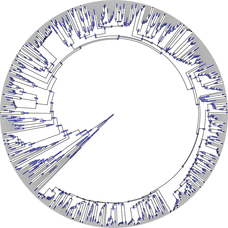

Our interests are not limited to species discovery. In addition to this, we want to infer the interrelationships within and among cryptic species complexes. With the advent of phylogenomics we are no longer limited in the amount of phylogenetic data we can collect (although analysis of these data is another matter). While I have published on the use of phylogenomic datasets to address the interrelationships of large clades of fishes, we will also be turning to a more exclusive route in my lab. We are fortunate to have whole genome sequences of species which span the blenny Tree of Life. We are currently planning to use this resource to develop a probe set which can be used to build species phylogenies at both shallow and deep time scales.

Our interests are not limited to species discovery. In addition to this, we want to infer the interrelationships within and among cryptic species complexes. With the advent of phylogenomics we are no longer limited in the amount of phylogenetic data we can collect (although analysis of these data is another matter). While I have published on the use of phylogenomic datasets to address the interrelationships of large clades of fishes, we will also be turning to a more exclusive route in my lab. We are fortunate to have whole genome sequences of species which span the blenny Tree of Life. We are currently planning to use this resource to develop a probe set which can be used to build species phylogenies at both shallow and deep time scales.

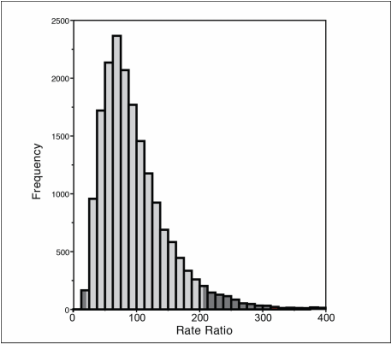

Posterior distribution of mitochondrial:nuclear substitution rate ratio

Posterior distribution of mitochondrial:nuclear substitution rate ratio

Molecular Evolution

Through the use of Bayesian divergence dating I have found that Acanthemblemaria blennies have a very fast mitochondrial substitution rate - over 25% sequence divergence per million years. This rapid rate is exclusive to the mitochondrion, which is evolving nearly 100 times faster than the nuclear genome. This mitochondrial rate has consequences that extend to speciation through epistasis between co-adapted mitochondrial and nuclear proteins. We are currently expanding upon these preliminary findings by performing high-throughput multiplex mtDNA genome sequencing for dozens of species and populations. We are also designing a probe set to capture the exons that encode proteins that directly interact with the mitochondrion. We will be able to perform comparative studies of mitochondrial and nuclear genome co-evolution with these data in hand.

Through the use of Bayesian divergence dating I have found that Acanthemblemaria blennies have a very fast mitochondrial substitution rate - over 25% sequence divergence per million years. This rapid rate is exclusive to the mitochondrion, which is evolving nearly 100 times faster than the nuclear genome. This mitochondrial rate has consequences that extend to speciation through epistasis between co-adapted mitochondrial and nuclear proteins. We are currently expanding upon these preliminary findings by performing high-throughput multiplex mtDNA genome sequencing for dozens of species and populations. We are also designing a probe set to capture the exons that encode proteins that directly interact with the mitochondrion. We will be able to perform comparative studies of mitochondrial and nuclear genome co-evolution with these data in hand.

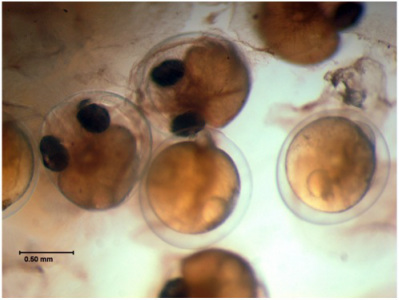

Acanthemblemaria aspera eggs 24 hours post-fertilization

Acanthemblemaria aspera eggs 24 hours post-fertilization

Hybrid Breakdown

Proteins encoded in the mitochondrial genome, such as those responsible for oxidative phosphorylation, directly interact with nuclear-encoded proteins. Gene products from each genome must be able to work properly with each other, or organismal breakdown will occur. Given their high rate of mitochondrial evolution, Acanthemblemaria is an ideal study group to answer whether hybrid fitness suffers due to poor interactions between mismatched mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. My lab is actively working on this with live animals. We are currently performing tests for hybrid breakdown of the offspring of crosses between different Caribbean populations of these fishes.

Previous Research

As part of my postdoctoral research in the lab of Tom Near, at Yale, I worked to resolve and measure the fish Tree of Life. Using genetic data from a large suite of nuclear genes, we built high-resolution phylogenies of all major groups in the fish Tree of Life. Through the use of dozens of fossil calibrations and relaxed molecular clock methods, these trees were used to estimate absolute ages of all major lineages, the timing of diversification in these groups, and identification of exceptionally species-rich clades of fishes. I also focused my efforts on resolving the relationships within and between families in a clade of fishes called Ovalentaria (described in Wainwright et al. 2012). Ovalentaria contains some of the most diverse and species-rich groups of fishes, such as cichlids, silversides, and blennies. In collaboration with Alan Lemmon and Emily Moriarty Lemmon, I used anchored hybrid enrichment and next generation sequencing technology to sequence hundreds of genes for all major Ovalentaria lineages. I used these data to build a species phylogeny of these Ovalentaria taxa. As blennies are members of Ovalentaria, I will still focus my research efforts on this clade.

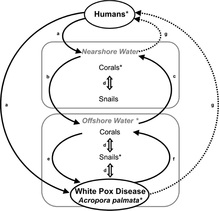

Coral reefs are in global decline due to disease. Understanding the causes and modes of disease transmission are essential to protecting reefs. Florida populations of the endangered Western Atlantic coral Acropora palmata have seen steep declines due to white pox disease, thought to be caused by the microbe Serratia marcescens. Found in human wastewater and with several vectors and reservoirs, I studied the transmission dynamics of Serratia on reefs in the Florida Keys. As part of my postdoctoral research in the labs of Erin Lipp and John Wares while at the University of Georgia, we used SNPs derived from Illumina and PacBio data from whole bacterial genomes to perform next-generation phylogeography and population genetic analyses. I am still collaborating with John and Erin with the goal of understanding the spatial and temporal mode of transmission of Serratia between human wastewater, vectors and reservoirs, and Acropora palmata itself.

In collaboration with Marshall Hayes, Margaret Miller, and my former advisor Michael Hellberg, I have worked on the population genetics of the threatened temperate coral genus Oculina. The deepwater Oculina population located at the Oculina Bank in Florida creates a unique habitat for associated taxa, but is threatened by anthropogenic disturbance in the form of trawling. Using nuclear sequence data, we found that the Oculina Bank population is genetically isolated from shallow water congeners. This suggests that reseeding from shallow water populations may not be possible and that further protection for the Oculina Bank is required.